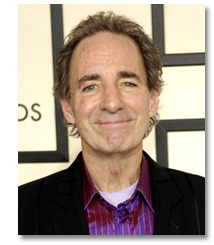

As Troy McClure would say, you might remember Harry Shearer from such Simpsons voices as Ned Flanders, Reverend Lovejoy, Mr. Burns, Waylon Smithers, Otto the Bus Driver, and Kang the Alien Octopus. You might also know him as the bassist from the heavy metal band Spinal Tap, author of the novel Not Enough Indians, and host of the radio show "Le Show," a one-man vocal circus in which Shearer talks politics with angry callers, insane guests and top-tier celebrities, all of them played by Shearer himself.

This week Shearer shifts gears, with the release of his new documentary The Big Uneasy, a serious, scientific look at how New Orleans flooded. With an investigative reporter's focus, Shearer hones in on the Army Corps of Engineers, the government agency that built the faulty levees that collapsed during Hurricane Katrina, flooding 80 percent of the city, killing more than 1,400 people.

The film features stunning internal memos, scientific reports and an interview with an Army Corps whistleblower to show that the Corps knew its levees were faulty and did virtually nothing to fix them. Instead of retrofitting the levee's walls and drainage system, the Corps spent millions on a public relations campaign trumpeting its own competence. It went to court to force a private company to install faulty levee walls, though the company objected, saying the walls would collapse in a storm.

The film features stunning internal memos, scientific reports and an interview with an Army Corps whistleblower to show that the Corps knew its levees were faulty and did virtually nothing to fix them. Instead of retrofitting the levee's walls and drainage system, the Corps spent millions on a public relations campaign trumpeting its own competence. It went to court to force a private company to install faulty levee walls, though the company objected, saying the walls would collapse in a storm.

The film ends on a chilling note: with congressional testimony from a top Army Corps official who tells Louisiana's senator, the Corps has no intention of fixing the long stretches of faulty levee walls that surround New Orleans today.

Shearer spoke with me about his movie, his radio wizardry, and the anger stirred by an American media that came to his new hometown but somehow overlooked the Army Corps' role in flooding it.

Kors: You're known for voicing goofballs, imitating celebrities, playing rock 'n' roll in a wig. This documentary, it's a big departure for you.

Shearer: It is. I do comedy for living. This is very different. But I love this city. And when you see a loved one get mugged, you don't walk away. Two teams of investigators spent a year doing forensic investigations on the flood, the levee collapse and I thought, "I have to get this out there." People need to know that, despite what they may have heard, this was a man-made disaster.

Kors: Now, you're originally from Los Angeles, then came to New Orleans in 1988. How did New Orleans come to be your hometown?

Shearer: Ah, they say, "You don't adopt New Orleans — New Orleans adopts you." There are few people who come because their boss transferred them here. This is a city of people who are here by choice, which makes the affection run that much deeper.

Kors: On your radio show, and now in this movie, you focus on the media, examining how the journalists erred so badly, reporting that this was a "once in a generation" storm when in reality, by the time Katrina hit New Orleans, the hurricane was relatively weak, between Category 2 and Category 1, the weakest of all hurricanes. How did the media get it so wrong?

Shearer: I think there are a few reasons. First, the final report with those findings came out much later, so it slipped past a lot of people's radar. When the reporters were here, they interviewed a few officials, then went to air. They didn't talk to the scientists, the experts who knew what really happened. The people here that were saying the Army Corps' levees were weak, they were made to look like kooks, colorful local folk, which made it all sound like folklore. I wanted to talk to the scientists who knew what they were talking about, who could tell me exactly what happened.

Kors: Initial reports on the Corps and the faultiness of the levees were pretty brief.

Shearer: Oh yeah. If the media mentioned it at all, it was a one-sentence reference: "Oh, by the way, the levees broke." As if it was an inevitability. The scientific investigation makes clear: this was a relatively weak hurricane confronting a levee riddled with construction and design flaws. ... I should say, it is a complicated story because at the same time, the full force of Katrina wrecked a large portion of the Gulf Coast: Mississippi, Alabama, Florida. So it was two stories, twinned in time, and the second story, of the natural disaster, essentially swallowed up the first.

Kors: Which is understandable. Still, as a journalist, I've been a little embarrassed by how the media covered the story. Most of what I know about the disaster comes from Spike Lee's extraordinary four-hour documentary, When the Levees Broke. I watched that film with my jaw dropped, wondering why it had so much information that wasn't there in the news coverage.

Shearer: I think what happened is a lot of reporters came, then left as soon as they thought they had the story. But they only had half the story. It was easy to go to the Superdome and file a report; it wasn't easy to get to the St. Bernard Parish and tell those stories. And after they split, they didn't pay attention as the reports came out, with the exception, I should say, of Brian Williams, whose recent report was a sort of mea culpa.

Kors: With the five-year anniversary, the media's attention is back on New Orleans.

Shearer: That's right. They keep coming back for the anniversaries — and keep repeating their own narrative: "There was a big natural disaster, etc., etc." It's embarrassing. But then, what are they going to say: "There's a horror here with levees the government knew were faulty... a fact we just happened not to tell you until now"?

Kors: Did you think about the resistance a movie like this would face, for a funny man to go make a sober documentary replete with scientific data? That's got to be a tough sell.

Shearer: It is. And that's partly why so many media outlets haven't gone into this information. Two quotes for me sum it up: a well-known anchor said to me, "You know, we'd cover the scientific information. We just think the emotional stories are more compelling." Another, a comment I got from a TV producer, he said, "What you're doing, that kind of sounds like a NatGeo sort of thing." So often, I think, the media condescends to its viewers, like they're too dumb to care about all that "science," all those "details." But I think people want to know this information. They want to know why the levees broke, why this city flooded. It may not be sexy, but it's settled science. It's what happened.

Kors: It's tricky because as a result, you can end up looking like an outlier, reporting events no one else is covering. I've run into that, covering how the military is pressing wounded soldiers to sign phony documents saying they had pre-existing conditions, or how the Army tortured an American soldier. Recently I had a top national reporter say to me, "We didn't cover that because if it really happened, we would have reported on it by now."

Shearer: (Shearer laughs.) Yeah, I ran into that years ago, working at Newsweek. I was an intern, and I remember calling up New York. I had uncovered a real news story, something people didn't know and needed to know. The New York editor basically laughed it off. He said it wasn't news because it hadn't been in the New York Times. ... I think the media's very aware of the role they play, shaping what's news. With New Orleans and the levees, you have the narrative. It's just not their narrative.

Kors: I'm wondering if you're familiar with Frank Relle, an extraordinary New Orleans photographer. He did some amazing work in the wake of Katrina, documenting the destruction with these haunting time-lapse photos of crumbling houses. The pictures are heartbreaking, but they're cast with this strange orange glow that's almost... beautiful.

Shearer: Interesting. I haven't seen his work, but that reminds me of Robert Polidori. His book After the Flood, it's stupefying. He toured New Orleans in a boat, while the city was still flooded. The subject was so horrific, but the photos he took were so beautiful. You want to look away, but you can't. Polidori's remarkable like that, to turn something so horrible and ugly into something beautiful.

Kors: On your radio show, amidst your parody segments — "41 Calling 43," "Clintonsomething," "Dick Cheney: Confidential" — you have a serious segment called "News From Outside the Bubble," where you look at important reporting that's slipped under the broader media radar. First, let me say, I was honored to have my reporting featured there in 2007, after it was picked up by the St. Louis newspaper. I'm wondering where the idea for that segment came from?

Shearer: It started during the run-up to the Iraq War. There were high-ranking officials who were openly questioning this weapons of mass destruction stuff, saying, "This is not what the evidence shows." But from the American media: nothing. I listened to that silence and thought, "Uh... hello?" With the British and Australian media, I had enough resources to know those officials' names, to learn things Americans weren't being told. And then I thought, "Hey, I have access to this info and to a microphone. Why don't I put these two things together?"

Kors: Inserting real reporting into a comedy show.

Shearer: Yeah. Up until that point, the show had been kind of flippant. I realized then it could be something more.

Kors: Do you feel like the media, even with all the hours of cable news, is still leaving a void, not covering important stories?

Shearer: Absolutely. I think the quality started to go down in the '80s, when the networks realized news could be a profit center. That was a definable moment, a turning point. Later, during the first Gulf War, CNN saw its ratings spike. They figured they could keep it up by maintaining the intensity, increasing the passion at the expense of information. Two decades later, instead of having real experts on the screen, every cable news show has a familiar group of partisans bickering at each other as if they know everything. And they do not know everything. But they're there because they have "passion." If you ever go on one of these shows, that's what they whisper in your ear: "Energy! Energy!"

Kors: I wrote an op-ed for Harvard's journalism quarterly about that model, the dueling partisans. The problem is: some stories are just about facts — there aren't two sides. The story of the Army Corps and its defective levees, that's a prime example. There aren't two sides to that story. The levees the Corps built simply didn't work.

Shearer: Right. And you don't have to abandon neutrality or fairness to report that. I went to the Army Corps and gave them a full opportunity to explain. I didn't have to load the film with one point of view. But the nature of their responses tells the story too. Anybody who watches this film and hears their explanation is going to have an easy time figuring out what went on. This movie isn't about what I think.

Kors: You're just a comedian.

Shearer: (Shearer laughs.) That's right. I'm just a fake heavy metal star. I say, don't take my word for it. Take the word of Dr. Bob Bea. He's been doing engineering and construction for 55 years.

Kors: Something completely different: I want to ask you about the "Silent Debates," your video series which features footage of Obama, McCain, Clinton and other prominent political figures during those long, awkward silences when the camera's on but the show has not yet gone to air. They're looking into the camera, they're a little jittery — and they're completely quiet. ... What was the idea behind that series?

Shearer: That was my attempt to get back to what TV is supposed to be: wallpaper for radio. We're a society that is so thoroughly documenting itself, and that means there's a great range of banal, empty footage. I thought, "Hmm, somebody should be collecting this stuff."

Kors: Is it your way of saying, "Look, you're not missing much. They're not talking — but when they were, they weren't saying much of anything anyway"?

Shearer: Ah, see, that's the thing about art: it's open to interpretation. In comedy, it's just the opposite: you have to be absolutely clear. You have a target, a point you're making, and sharp comedy drills that home. With my art, it's better for me not to interpret, let the audience decide what they make of it.

Kors: You have to forgive me for being so stupid, but it was a few weeks of listening to your radio show before I realized that every guest you had on, every listener who called to complain, they were all you — you cutting yourself off, telling yourself never to call again.

Shearer: It's fun, isn't it?

Kors: It is. You said once that that format was inspired by another radio host who did multiple voices on his show.

Shearer: Yes, Phil Hendrie. I've been a fan of his for years. He's been doing a live radio show for decades now. He'll pretend to be fake callers, play fake experts saying the most outrageous things, then take calls from real people who are enraged by the experts' comments. It's amazing stuff.

Kors: In your show, you keep your focus pretty tight on politics. You never dip into celebrity sagas — Lindsay Lohan or Justin Bieber — though I imagine that might draw good ratings, improve your search engine optimization.

Shearer: That's true. And you'll notice, I didn't mention one word this week about Glenn Beck and his "Restoring Honor" rally. I talk about what I care about, the subject I know about. The world doesn't need any more half-assed opinions. If people have cable, they've got enough of that already.

Kors: Still, there are people — a lot of them, I think — who would never go to a movie about Katrina. They want news that's light and fun. What do you say to them?

Shearer: I'd say, this movie is about them too. Their federal tax money — the money that built these levees — went to this city to save it. Instead it almost destroyed it. And it's not just New Orleans. The Army Corps' shoddy work is in dozens of cities around this country: Sacramento, Dallas. This isn't a New Orleans story — it's an American story.

Note: To commemorate the fifth anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, The Big Uneasy was released in theaters for a one-day-only event. For updated info on future showtimes and the film's DVD release, visit Shearer's official website and TheBigUneasy.com.

Follow Joshua Kors on Facebook: www.facebook.com/joshua.kors